Warning: Strong language, profanity and offensive imagery

Americans love origin tales. As of late the most popular have been about super heroes, like Batman or the X-Men, or our most beloved villains. Certainly Star Wars fans flocked to screens to witness Anakin Skywalker’s transformation to Darth Vader. This duality of heroes and villains fits nicely with the origin story occupying my mind these days, the origins of the Ku Klux Klan in D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915). In the film, black children frightened by two young white pranksters inspire Ben Cameron to create the Reconstruction-era terrorist group.

Historically, the Klan first appeared in Pulaski, Tennessee in 1866. By 1868, the group infiltrated South Carolina, most notably in the upcountry. By the early 1870s, the federal government drove the group underground through legislation and trials aimed specifically at making an example of South Carolina, although few members were ever convicted.[1] I am not the only one debating Griffith’s manipulation of the Klan’s origins. Quentin Tarantino directly entered into humorous conversation with Griffith through a scene in Django Unchained (2012), which features a pre-Klan group of regulators before the Civil War.

Tarantino confessed to Henry Louis Gates, Jr. his desire to “deconstruct” The Birth of a Nation.[2] But while the regulators led by Jonah Hill and Don Johnson elicited laughter from the audience, Tarantino’s frustration with the legacy of Birth and disdain for director Griffith and screenwriter Thomas Dixon is no joke. John Hope Franklin believed Birth was “Dixon, all Dixon.” Gates and Tarantino found Dixon’s influence, via his original work The Clansman, to be “evil.”[3] Tarantino explained:

“. . . you have to understand, I’m obsessed with The Birth of a Nation and its making . . . I think it gave rebirth to the Klan and all the blood that was spilled throughout—until the early 1960s, practically. I think that both Rev. Thomas Dixon Jr. and D.W. Griffith, if they were held by Nuremberg Laws, they would be guilty of war crimes for making that movie because of what they created there . . . But I’ve written a big piece that I’ve never finished that is about the thought process that would go into making The Birth of a Nation, and you know, it’s one thing for the grandson of a bloody Confederate officer to bemoan how times have changed—some racist Southern old-timer bemoaning how life has changed, complaining that there was a day when you never saw a nigger on Main Street, and now you do. Well, if he’s just going to sit on his porch and sit in his rocking chair and pop off lies, who cares? That’s not making The Birth of a Nation every day for a year, and financing it yourself. And if you ever tried to read The Clansman, it really can only stand next to Mein Kampf when it comes to its ugly imagery.”[4]

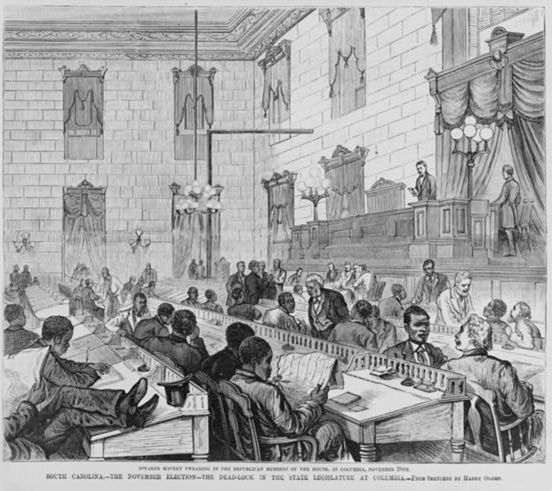

I pondered on whether Tarantino knew Dixon actually tried to have the film remade as a talking version in 1933.[5] Then I smiled at the notion that Tarantino and I both ruminate on the making of Birth and the origin of domestic terrorism at the hands of white supremacists. I am beginning to look at the film in a new way, from a regional perspective. Although The Birth of a Nation is fictional, it is intentionally set in South Carolina in the imagined community of Piedmont. One of my favorite professors Dr. Susan Courtney once said about Birth’s setting that it was “somewhere, down there, in South Carolina” as if the state stimulated mystical notions of place for film goers. What happens to the interpretation of the film once I dismiss the mythical South Carolina and begin to think of the film in terms of nationalizing South Carolina’s white memory of Reconstruction? Evidence of historical South Carolina emerges and an obvious real representation of Columbia manifests itself in the scene within the capital’s State House. Griffith reveals to the audience that he created a historical facsimile of an authentic legislature based on a picture from the local newspaper. The clip as well as an illustration of the legislature awaiting results during the disputed 1876 election demonstrate Griffith’s ability to stretch historical realities to mythical proportions.

South Carolina–the November Election–the Dead-Lock in the State Legislature at Columbia by Harry Ogden. From Frank Leslie’s Illustrated, v. 43 (1876 December 16), cover. Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Online Catalog.

Griffith, a Southerner, took a Southern work, largely consumed by Southerners, and nationalized it with the help of non-Southern producers and film executives. The highest earning silent movie of all time, the film reached 200 million people by the end of World War II. Griffith in fact sought out elite, middle class, and reform audiences not only by insisting on screenings in opera houses and respectable theaters but also by emphasizing the epic nature of the film as well as its conforming to Victorian notions of respectability and morality.[6] Thus, Griffith needed to appropriate a universal white supremacist narrative that would resonate with audiences and be easily understood. Given the Klan spread across the South and into media of the Reconstruction era, the group offered a straightforward symbol recognized by millions of Americans as the nation attempted to negotiate whiteness and middle class values during the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

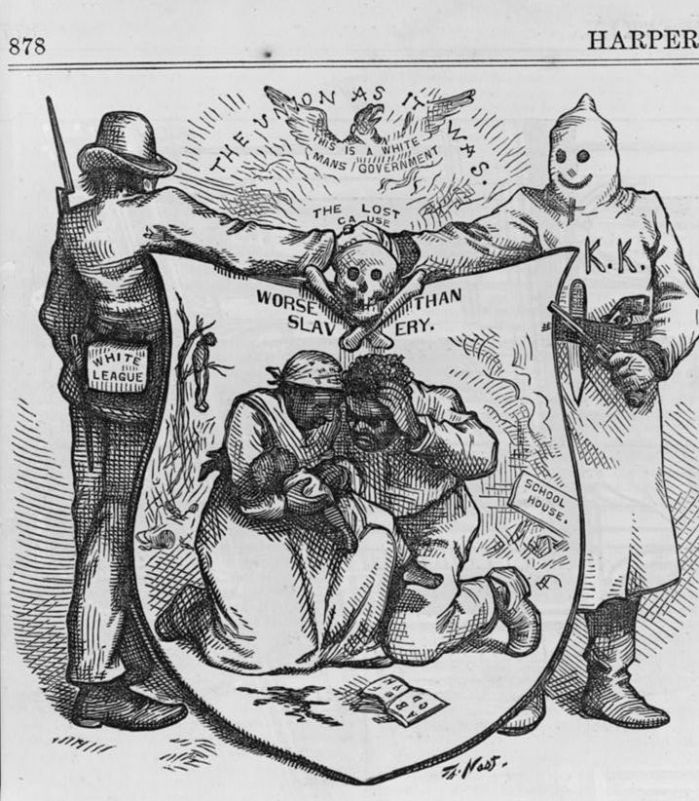

The Union as It Was the Lost Cause, Worse Than Slavery by Thomas Nast. From Harper’s Weekly, v. 18, no. 930 (1874 October 24), 848. Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Online Catalog.

But anyone who knew South Carolina’s Reconstruction history, and certainly Griffith and Dixon knew some, would be aware that the state’s Democratic Party supported by the terrorism of the Red Shirts, not the Klan, toppled Republican-ruled Reconstruction in the state in 1876. What if Griffith’s and Dixon’s veiled origin tale is that of South Carolina’s Red Shirts and not the KKK because to tell an authentic history of Reconstruction’s end in South Carolina proved too complex for national consumption? Did South Carolinians imagine the Red Shirts when they watched the film? Furthermore, did Woodrow Wilson, who grew up in Columbia during Reconstruction and attended graduate school with Dixon, recall his own childhood in the capital city when he screened the film in the White House at the request of Dixon and producers? Amy Wood argued white audiences received the film as more than a cinematic masterpiece. Birth offered historical truth, an idea promoted by Griffith. White film goers not only experienced the unprecedented realism of Griffith’s version of the Civil War and Reconstruction, but they also understood the white supremacist and pro-lynching imagery in relation to their own contemporary fears.[7] The film exposed Lost Cause ideology and presented a defense of Jim Crow to nationwide audiences through melodrama that made these ideas palatable to Victorian-era whites.[8] White Southerners, who at times rejected the play version of The Clansman because it did not speak as effectively to Lost Cause ideology or have a documentary feel, embraced Birth. Viewers in Atlanta saw themselves as “active witnesses to history.”[9] Furthermore, white Southern audiences connected with the film more intensely because the melodrama fed their own manufactured historical version of the past and anxieties about the black vote, crime, and sexuality. Thus, audiences at times suffered from “overidentification” with the characters.[10] South Carolina historian John Hammond Moore once wrote about a screening in Spartanburg, South Carolina describing the scene of former Confederates and other men who once donned “white sheets, and red shirts” as they shot the screen to protect virginal belle Flora Cameron from Gus’s sexual assault.[11] I will continue to explore this question in future blogs. Hopefully new sources will come to light that will allow me to gauge reception of Birth in South Carolina. In the meantime, I will continue to dissect the film itself and look for visual clues that speak to how the influential film packaged and modified a regional tale of white supremacy for national consumption.

[1] Walter B. Edgar, South Carolina: A History (Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press, 1998), 398, 400–401.

[2] Glenda R. Carpio, “‘I Like the Way You Die, Boy’: Fantasy’s Role in Django Unchained,” Transition 112, no. 1 (2013): 1; Henry Louis Gates Jr., “‘An Unfathomable Place’: A Conversation with Quentin Tarantino about Django Unchained (2012),” Transition 112, no. 1 (2013): 53.

[3] Karen L. Cox, Dreaming of Dixie: How the South Was Created in American Popular Culture (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011), 83; Gates Jr., “An Unfathomable Place,” 52.

[4] Gates Jr., “An Unfathomable Place,” 51–52.

[5] Cox, Dreaming of Dixie, 176.

[6] Ibid., 85; Amy Louise Wood, “With the Roar of Thunder: The Birth of a Nation,” in Lynching and Spectacle: Witnessing Racial Violence in America, 1890-1940, New Directions in Southern Studies (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009), 160–161.

[7] Wood, “With the Roar of Thunder: The Birth of a Nation,” 149–150, 170.

[8] Ibid., 155, 159; Cox, Dreaming of Dixie, 84.

[9] Wood, “With the Roar of Thunder: The Birth of a Nation,” 150.

[10] Ibid., 153, 165–167.

[11] Ibid., 166. Wood cited John Hammond Moore, “South Carolina’s Reaction to the Photoplay ‘Birth of a Nation.’” Proceedings, South Carolina Historical Association (1963), 30. Reprinted in Lander and Ackerman, Perspectives in South Carolina History: The First 300 Years (Columbia 1973): 337-47.”

Great post here. I am intrigued by those questions that you raised, especially about whether Wilson would have thought about Columbia. I am now thinking about how to possibly weave that into my tour. We have been reading a lot about the idea of southern tradition in the southern studies course and this makes me think about that. The way that these sort of Lost Cause narratives played into and reinforced southern ideas and notions as that is simply the way that things were, you simply do not question which is why this had such a powerful affect on people.

LikeLike

Pingback: Finding Columbia in The Birth of a Nation | Reconstructing Reconstruction